Thousand sensors to watch over our world

Opinion editorial by Assela Pathirana, Chief Technical Engineer - Water Engineering at UNDP Maldives.

"We need science education to produce scientists, but we need it equally to create literacy in the public. … Such participation was quite common in the 19th century but has unhappily declined. Literacy in science will enrich a person’s life."

– Hans A. Bethe (Nobel laureate, 1967)

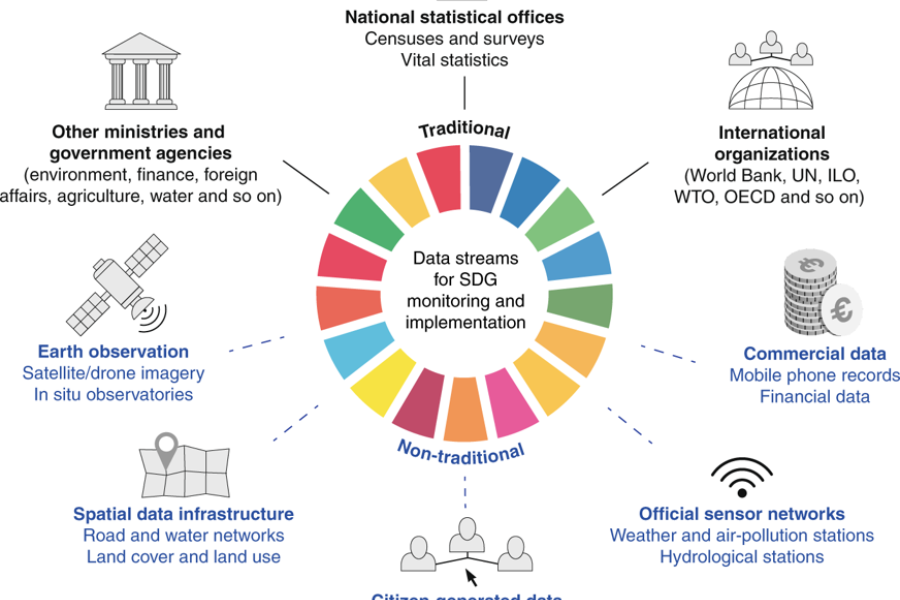

“Small islands do not have sufficient environmental data” – I have heard variations of this hundreds of times. The subject of the particular statement could be developing-countries, global south, megacities or rural villages – it’s a reality we complain about a lot! And with good reason. We’d like to have credible, plentiful information, be it to understand the problems we try to solve or to monitor how effective our solutions are, we in the business of sustainable development sector are always data thirsty! Gathering data is a matter of spending time and money. But there lies the problem. The finite amount of resources we have should be divided between data gathering and really doing something. So, we don’t have unlimited time or resources to perfectly understand the world around us – we need to act too.

We live in a rapidly changing world. Climate is changing fast. Cities grow. Populations migrate. Weather patterns change. Once in a while the nature throws in a shock like COVID-19 for good measure! The environmental, social and economic data that we base our development decisions get rapidly outdated. That makes it necessary to keep on collecting data practically nonstop. To do this cost effectively we often have to look outside the box.

The Maldives has more than 180 inhabited islands with many with populations less than 1000 inhabitants. Less populations do not mean they are facing lesser challenges to the sustainability or lower rate of change. In fact, these are among the most climate-vulnerable places on the earth and undergoing rapid change that need to be continuously monitored. But the challenge is every rufiyaa allocated for monitoring the vulnerability is money taken away from addressing the same vulnerability – a zero sum game. Therefore, in the Maldives we need to continuously innovate on cost-effective, but also EFFECTIVE, ways of doing environmental monitoring.

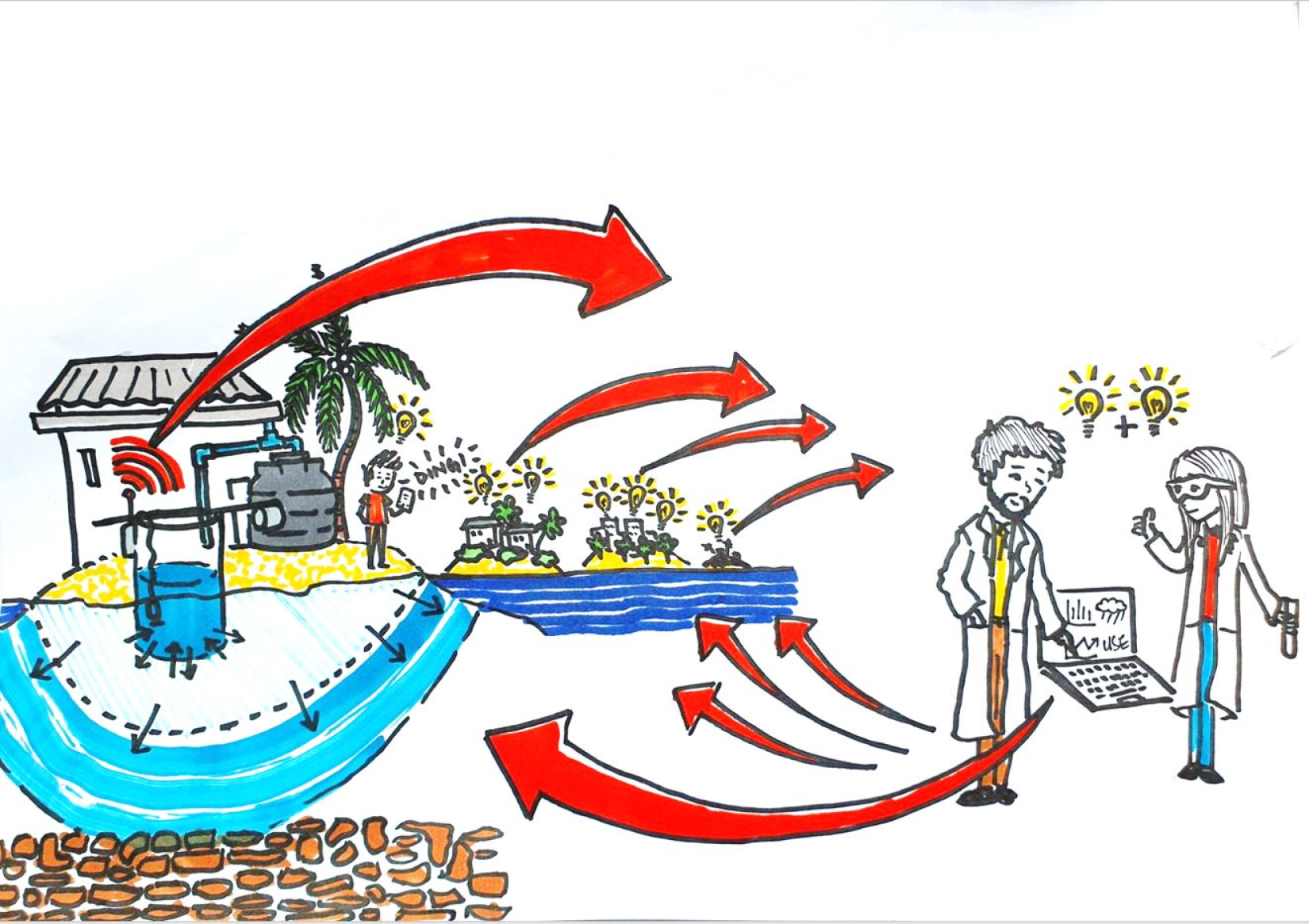

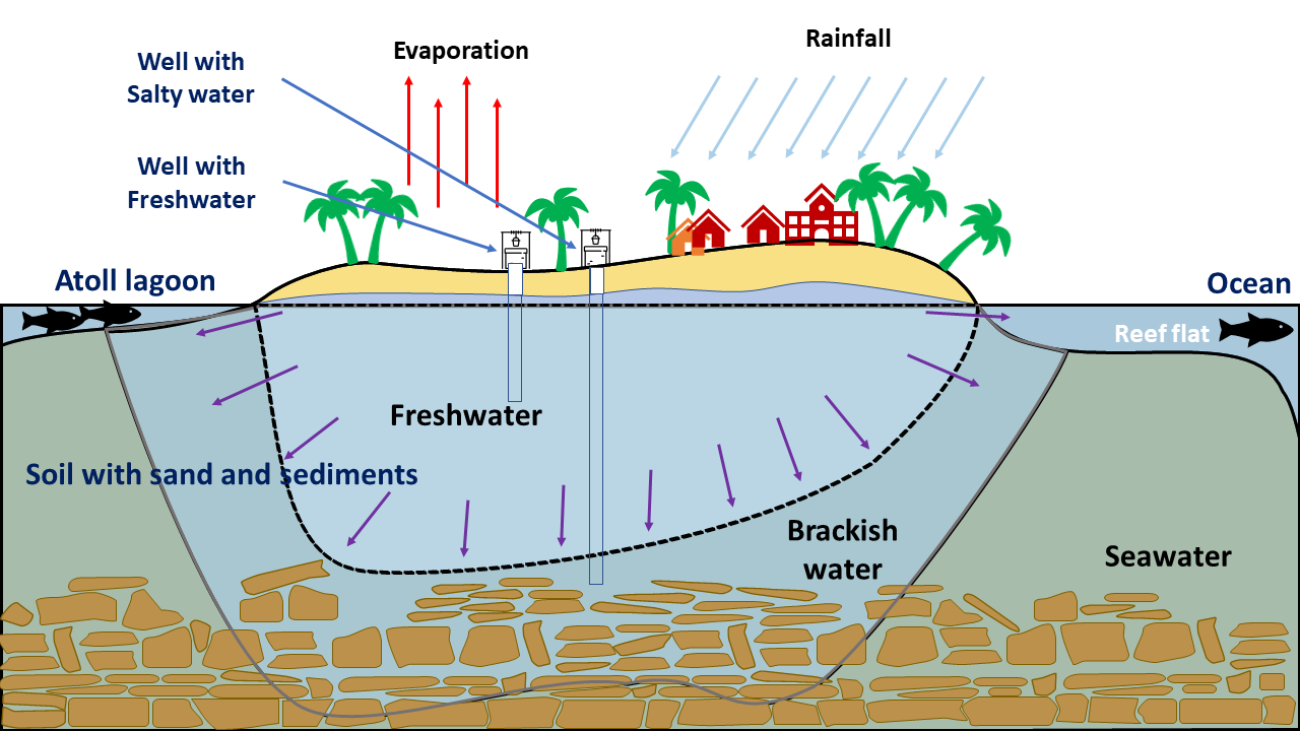

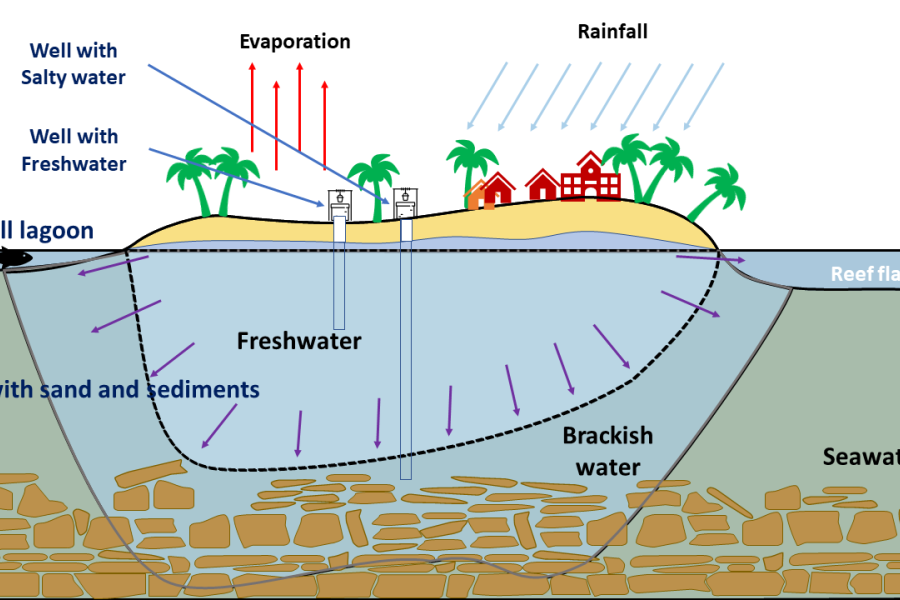

Under the project by Ministry of Environment supported by UNDP, “Supporting vulnerable communities in Maldives to manage climate change-induced water shortages” we practically faced this exact same challenge: The water security of 25 inhabited islands being addressed by the project. One of the important, yet elusive, factors of water security in outer islands of the Maldives is their so-called “freshwater lens”. Amount of freshwater underground fluctuates seasonally. But there are long-term trends too. Climate change and human activities impact the health of the freshwater lens. Monitoring these changes is an important integral part of responding to the water security challenges. But such monitoring is costly. It involves sophisticated scientific equipment and several days of expert involvement for each island.

But can we enlist the help of the inhabitants of these islands to do the monitoring of the groundwater resources. A simple idea: Every household that has a groundwater well (nearly 100% in many islands) is a potential sensor of the health of the freshwater lens. We just have to enlist their support and suddenly we have thousand sensors to monitor our resources! This is exactly what we did. We surveyed more than 2100 households from the 45 islands and inquired them how they perceived the groundwater they obtain from the family wells. Does it smell? Looks clear? Do they use it for drinking and cooking? Washing, bathing and toilet flushing? We went on. The result was a dataset that revealed plenty of useful information.

Let’s understand this in the right context: Conducting a onetime technical groundwater investigation in a single island costs thousands of dollars. We do that sometimes. However, this is not an approach that we can use to monitor the groundwater day-in, day-out, all over the islands. Its simply too expensive for that. But do we have to be limited by technical investigations? Alongside those, why not engage the island community as thousands of living sensors? We realized this is possible.

And we are in good company. Thousands of environmental scientists around the world are increasingly relying on ‘citizen science’. Scientists in Japan have enlisted the help of thousands of volunteers in the Fukushima disaster region to collect more than 40 million radiation data points. In the USA scientists enlist volunteers to collect environmental data that helps to detect faulty septic systems, improper wastewater treatment plant discharges and illegal connections in municipal stormwater systems. Flanders environmental agency in Belgium enlisted 20000 households to continuously measure nitrogen dioxide – a poisonous gas resulting from urban pollution – levels at their streets. Central Caribbean Marine Institute enlists community scuba divers as volunteers to collect important data on coral reef health. The list is long and growing.

Our efforts to involve citizens go beyond just enlisting them to collect data. After all, these same individuals who help us by volunteering to be ‘sensors’ are also critically important in taking proactive action to address the environmental issue that are surfaced. Take the example of the fragile freshwater lens: The quantity of fresh water critically depend on how much rainwater is allowed to seep into the ground. Increasing development activities like construction of buildings and roads generally reduce the seepage and therefore groundwater recharge. Now, effectively doing this involves very close collaboration with and support of the very islanders who helps us with data. One of the surefire ways of enlisting the support of citizens is to empower them with knowledge. What better way to do this than involving them in the monitoring activities? Of course, this goes beyond mere data gathering. It involves learning and sharing knowledge in the community. That’s how it is possible to use citizen science to make science more democratic!